30 Fingers: The Tijuana-San Diego Borderland

Written By: MIMS Cohort 7 student Tay Ingersoll

From February 16th-18th 2024, MIMS students and USF faculty traveled to the San Diego-Tijuana (TJ) border to meet with nonprofit organizations which serve to humanize and dignify migrants transiting along the southern border.

We began our journey at the University of San Diego where we met with MIMS Cohort 1 alumni, Maria Silva, who currently works for the IRC, International Rescue Committee. Maria shared the IRC processes for supporting and resettling newly released migrants from Customs and Border Patrol detention. In San Diego alone, between 600-800 migrants are released per day on the streets of the city. NGOs received county funding to coordinating a specific reception site where new arrivals could receive resources in one location such as financial support to book airfare to their final transit destination. Maria says, “95% of people do not intend on resettling in San Diego but to move to cities such as New York City, Los Angeles, Miami or Atlanta.” In the month of January 2024, altogether 16,000 migrants arrived at this day center seeking assistance. 17% were from China, 16% Colombia, 8.2% India and 6.7% from Turkey. Maria is an example to MIMS students on how to put knowledge and passion into the field of migration.

Soon after, we drove to San Ysidro in South San Diego. There, we met with organizer Hector Castro at the FRONT Arte Cultura at Casa Familiar, where he shared about this inspiring art collaborative. Artists along both sides of the US-Mexico border share their work in this exhibition space, which truly works to uplift local voices. The center is a place for community building and connection. Between formally incarcerated youth performing art shows to bringing pieces across the border to share, the gallery serves as a platform for portraying culture and resilience in this border community.

Our group then set off on foot for a 30 minute trek toward the San Ysidro border crossing point of entry. Our destination in sight was the local Jack in the Box where we followed a path behind the restaurant toward a large sign saying “Mexico”, followed by tall gates adorned with spirals of barbed wire. Even a strange art instillation overhead of pointed triangles, like jagged spears, a symbol of control and disconnection. Once we waited shortly, showed our passports and crossed into Tijuana, we were greeted by our weekend van driver Jesús, who drove us to Casa de Manresa on the IBERO campus. It was eery driving next to the tall, unnatural border wall which weaved across hillsides and coastal terrain. We soon arrived at our residence and enjoyed a beautiful view of the sun setting along the ocean. A sight so peaceful yet you cannot help but be reflective on what is happening mere miles away.

We gathered for dinner and enjoyed the company of attorneys Nicole Elizabeth Ramos and Soraya Vazquez who represent Al Otro Lado, a non-profit organization providing holistic legal and humanitarian support to refugees, deportees, and other migrants in the US and in Tijuana. They shared their commitment for this work and the injustices they repeatedly witness along the border. It is heartening to meet with the representatives who provide essential, free legal information and assistance to those who have been deported and those seeking asylum in the United States. Their efforts make such an impact along the border!

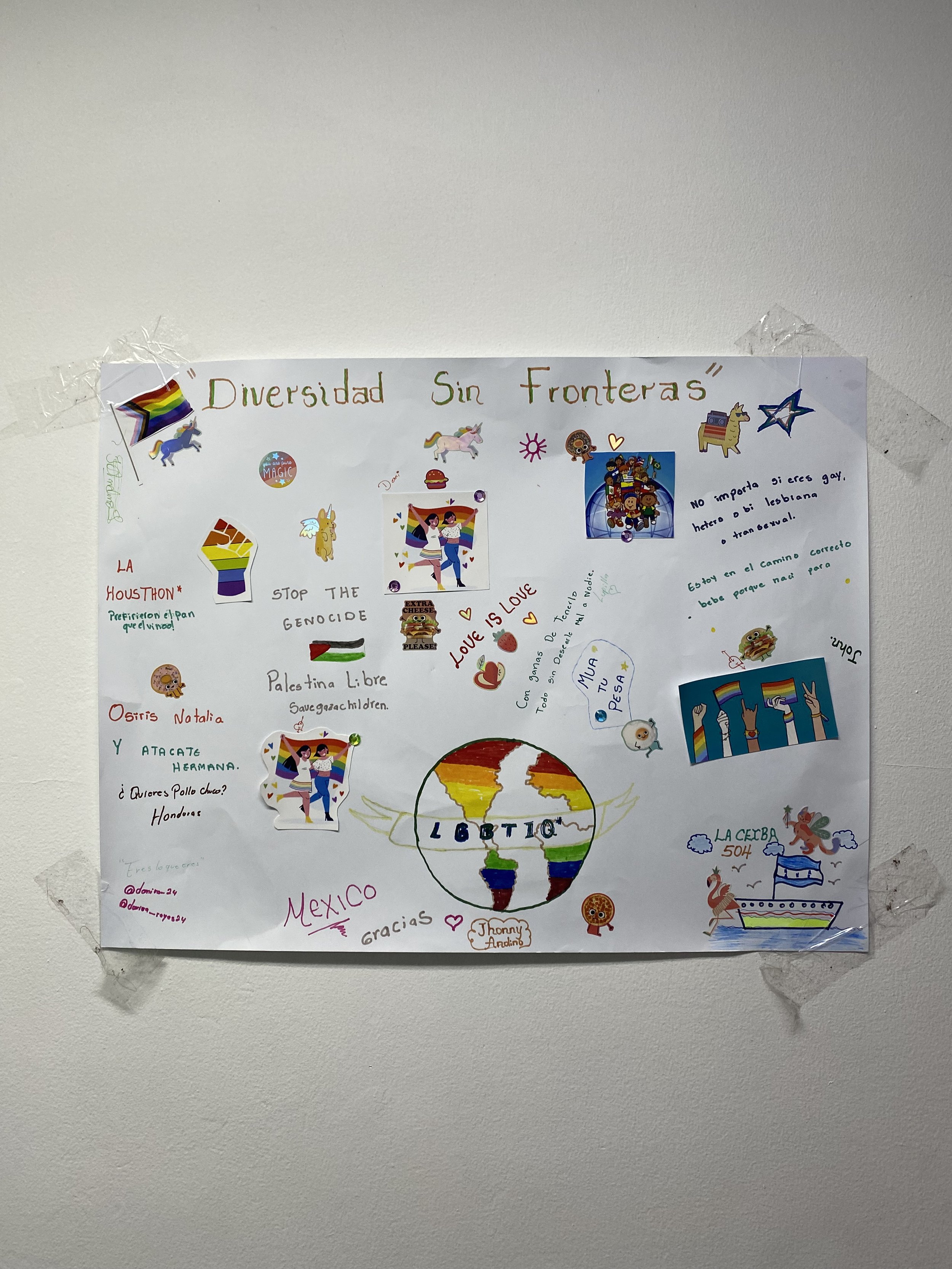

The next morning our group set off to Casa de Luz Tijuana where we met with founder and director Irving Mondragón. This is a safe house which provides shelter, food and resources for LGBTQIA+ asylum seekers transiting through Tijuana. The grassroots organization was created 5 years ago after an influx of over 6,000 migrants crossed into Tijuana via caravans. This was also during the time President Trump issued the Migrant Protection Protocols, or MPP, as a way to manage undocumented migration along the US-Mexico border. When the Biden administration took over, Casa de Luz decided to start an encampment at the El Chaparral point of entry when Biden said 300 asylum seekers could cross per day. Mexican authorities started sending migrants to the shelter, over 7,000 asylum seekers including 37 nationalities. The space began to become out of control and overwhelmed, so organizers remodeled 3 apartments into housing for queer migrants over a year and a half ago as a solidarity space. With 21 rooms, the shelter can hold roughly 40 individuals. However, there is still a culture of scrutiny toward the LGBT community between conservative neighbors, lack of access to HIV medication and even censorship on social media. Casa de Luz staff work effortlessly to protect the queer asylum seeker community and advocate for social justice and human rights.

Our next stop was La Casita Tijuana where we met with founder Susana ‘Susy’ Barrales. As a trans woman, she understands the needs of trans migrants; safe and secure shelter, name change services, access to free hormone therapy treatment, mental health resources and simply a community of inclusivity. Susy began offering workshops like trades of barbering and baking, educating people to have the tools they need that they didn’t have the opportunity to study in school. La Casita also started projects centering trans mental health and emotions. If you want to finish primary and middle school they can help, they look for safe places to work for trans women and follow up with women who have transited in their migratory journey, especially if they have reliance on medical care. The Mexican government still criminalizes trans women by using their dead names and by not recognizing gender change even when showing proper documentation. Susy started La Casita after being deported to TJ since living in the United States for over 25 years. She began offering sanctuary to trans women outside of her bedroom and women kept showing up and the organization simply flourished as a pathway for sanctuary. “There is a lot of love in La Casita, this space saves lives”, says Susy and we are grateful and inspired to witness her success.

The last organization we met that evening was Aldeas Infantiles SOS Tijuana, an international NGO founded in Austria after WWII in 1949. Founder Hermann Gmeiner saw lots of kids without parents and parents without kids after the war, and thought it would be a good idea to blend the two. He created a small housing village model as a reminder of what community felt like. Today in Tijuana, lead organizer and psychologist, Berenice Castro, shares the structure of the village, the criteria for family admittance and the rules of the community. The organization partnered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) from May 2020 until December 2023 to work with families who had or would have refugee status in Mexico. If Aldeas Infantiles receives an unaccompanied minor, they would bring the minor and a caretaker from the village in Mexico City to Tijuana and have them await their asylum there until they could be reunified with their family in the United States. The village can house up to 77 people and aims to put families where it is in the best interest of the child. Typically two family units would share a single housing dwelling. For instance, housing a single mother with 3 children younger than 10 years old with another single mom with children of similar ages. The village always keeps in mind any religious practices, cultural identities, language, and dietary needs when housing families together. The model aspires to highlight migrant agency and independence for individuals to make the home their own. A workshop is offered for psychosocial accompaniment and positive parenting and there is a zero tolerance policy for any type of violence. The staff helps parents find jobs by searching for the best profile for employment and children must be enrolled in school. Families may leave the premises at anytime but can only stay up to 3 months while waiting for asylum. The goal is for families to have a sanctuary, save money and get assistance and resources to plan out their next transition. Criteria for admittance is to remain in Mexico while seeking asylum, be in well physical and mental health, to have children and at least one member of the family must speak Spanish. Families come from Iraq, Spain, Colombia, El Salvador, Cuba, Guatemala, and Haiti. Sharing homes can be tricky but Aldeas Infantiles SOS Tijuana created a garden of love and light to welcome newcomer migrant families and continues to support their needs along their migratory journey.

On the last day of the border trip, we visited Border Market in Playas for breakfast. Gaba Cortes, artivist and immigrant advocate, shared her founded space which invites migrants along the border to enjoy company and coffee together. She was inspired by migrant food shelters, “No matter where you are from you can share food with anyone”, shares Gaba. We learned over 1,500 people have visited Border Market, to come enjoy a cup of coffee on the balcony and not be bothered by police on the streets. The networking has grown through word of mouth about this coffee refuge. Gaba reiterates that food does not have borders as we sit in community munching on delicious mole chilaquiles and pambazos. She shared the various striking murals which line the walls, all of local activists who have fought for immigrant justice. She says, “Sometimes we cannot be present in person but we can be present in other ways.” Gaba is an example of an artivist in our work, making art that focuses on underrepresented narratives, sending a message of migrant resistance to advocate for change. Finally, we left from Border Market down to the border wall along the beach, about a 15 minute walk.

“I feel so grounded at the beach, it’s a familiarity that’s safe and calm. This feeling which soon dissolved into numbness and pain. I felt the cool water grab my ankles and slowly drift away. Then we were there, the moment I was anticipating: seeing the border wall. I kept looking out at the crashing waves which broke onto the end of the wall, less than 100 yards away. I sat with some peers along the wall’s edge, staring at names which were engraved into the metal. Almost how lovers carve their name into a tree. I soon walked up along the wall when I arrived at the U.S. deported veterans mural. My gut sank. Being a veteran myself, it brings me overwhelming feelings of anger and grief that the country I served could treat their service men and women this way. The wall is a symbol of division and dehumanization. There needs to be a dismantling of this cruel barrier.” -Tay Ingersoll MIMS Cohort 7

We received a spontaneous introduction to Border Church, a ministry which started 4 years ago. Sermons are held in front of the wall where people come for safety and peace. Pastor Guillermo Navarrete, lay leader with the Methodist Church of Mexico and lead pastor of Border Church in TJ, unites congregations to include LGBTQIA+ migrants and deported veterans. He shared an incredibly heartbreaking story of his time serving the church. He met a deported veteran sitting on the ground against the border wall waiting to see his wife and three daughters on the other side. Guillermo asked our group, “Do you know how people kiss each other through the border wall?.” We looked left and right at each other questioning alternative ways to show love. He raises his two pinky fingers and joins the ends together. He said he remembered seeing the deported vet “kissing” 30 fingers when his daughters eagerly arrived on the other side. The wall continues to enforce family separation and perpetuates the anguish and trauma experienced by countless individuals seeking refuge and safety along the southern border.

Our group made way to the El Chaparral point of entry around 1:15 PM. We waited nearly 30 minutes in line and were no more than 30 people away from accessing customs. However, the port decided to close at 1:40 PM instead of 2:00 PM, forcing us to walk 20 minutes to the San Ysidro facility. It was bizarre that they would not even let a young teenage girl ahead of us, who was next in line go through when her father was already inside, a sight of reality for many crossing the border. We quickly made our way over to San Ysidro, having prior knowledge the wait could be long and some students had upcoming flights. We waited under 2 hours in a line swarmed by local vendors selling tortas, churros and hand crafted goods. I later learned that these crossings could take up to 4 hours at times. It goes to show the barriers and challenges that the United States enforces toward those crossing the southern border.

As our experience to the San Diego-Tijuana border drew to a close, one thing became abundantly clear: the power of human connection transcends borders. Through sharing testimonies and living experiences, we made connections that carried our passion for advocating and supporting migration. As we departed, we carried with us not only memories but also a commitment to continue the vital work of advocacy and solidarity. Thank you to everyone who made this experience possible and educating our group on the complex realities within this borderland.

Organization Links